Battle of Mactan Beyond Textbooks

Posted on 27 April 2021

By Van Ybiernas and Xiao Chua

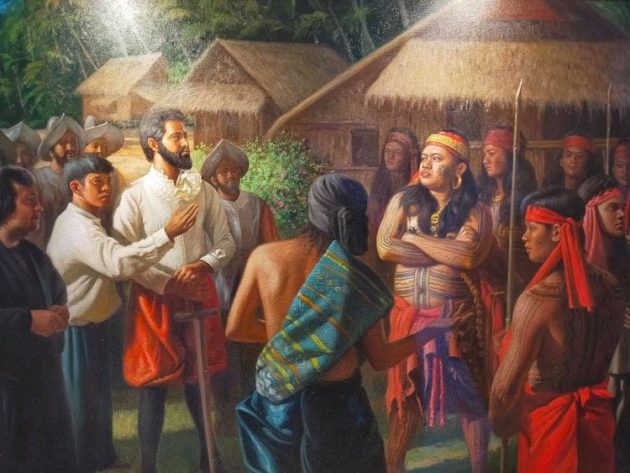

Because of his expedition’s battle-ready impression, Ferdinand Magellan did his best to cast away our ancestors’ fears by limiting their firing to ceremonial purposes. King Carlos’ instruction to Magellan was clear: be friendly to the natives of the territories they visited. Guided by the king’s order, the expedition proceeded to Cebu, an ancient Southeast Asian port. Without any means to pay an anchorage fee, Magellan instead won the paramount ruler of Cebu, Rajah Humabon, by bragging about the might of Spain and that it could help the rajah gain greater influence, at least, in the Visayas. Convinced that Spain was more powerful compared to the conqueror of Calcutta and Malacca—Portugal—Rajah Humabon welcomed Magellan and was even persuaded to accept Christianity. Magellan fed Humabon’s self-esteem with assurances of becoming the lord of as many communities as he pleased and the destruction of those who would reject his lordship.

To test the adherence to Rajah Humabon, a ruler must present Magellan tributes and food supplies. Rulers from the suburbs of Cebu, including Mactan under a chieftain named Zula, came in and brought Magellan what the expedition needed to the best of their ability. Pigafetta identified some of these rulers as Cilaton, Ciguibucan, Cimaningha, Cimatichat, and Cicanbul of Cinghapola, Apanoaan of Mandaui (Mandaue), Theteu of Lalan (Liloan), Tapan of Lalutan, Acibagalen of Cot-cot, and Apanoan of Puzzo. Although unnamed, the rulers of Cilumai and Lubucun also presented tributes to Magellan.

On 26 April 1521, Magellan received the son of Zula with only two goats as presents. That son of Zula reported that his father failed to provide what he promised to Magellan because another chief of Mactan named Çilapulapu (henceforth referred to as Lapulapu) refused to recognize the king of Spain. Lapulapu declined to give Magellan “three goats, three pigs, three loads of rice, and three loads of millet” for the three naos (Spanish ships) of the expedition. Zula also conveyed his request to Magellan to send troops to punish Lapulapu. Midnight of the same day, Magellan and his 60-strong force, together with Rajah Humabon, some princes, and his very own men, riding in several balanghai (ancient Philippine boat), left for Mactan.

The Showdown in Mactan

Magellan and his group anchored in Mactan before dawn on 27 April 1521. Because of the low tide and the terraces of corals, “the boats could not come closer to the beach,” written by Pigafetta who also joined Magellan in fighting Lapulapu. Through the Muslim merchant who already served as their translator, Magellan sent an ultimatum to Lapulapu to subject himself to the authority of Spain to avoid the destruction of Mactan. It was simply ignored by the chief of Mactan. Thus, Magellan and 49 of his men, including Pigafetta, waded in the water for more than a kilometer until they reached the shore. Humabon offered Magellan assistance, only to be told to back off and just watch.

Magellan’s force relied only on two weapons: escopetas (harquebus gun) and a ballesta (crossbow), the latter’s use forbidden then by the Church because of its brutal effects except if used against non-Christians. His decision to leave behind the naos (ships), which were almost eight kilometers away from the Mactan shore, only showed his inability to lead a force. Historian Danilo Gerona described Magellan’s Armada de Maluco as a “floating arsenal… armed with the most powerful artilleries of their time” that could have been utilized for a long-range naval battle.

As they approached the shore, Magellan’s men fired crossbow bolts upon Lapulapu’s 1,500-strong force (as estimated by Pigafetta) arranged in three divisions. However, shots failed to penetrate the shields of our ancestors, thus Magallanes ordered us to keep from firing ballesta.

(Hangaway was the term for the ancient Visayans for warriors, whose bodies were usually decorated with batek or tattoo, thus the Spaniards called them Pintados. The 16th-century Boxer Codex of the Lilly Library at Indiana University has an illustration of them. This illustration served as inspiration for the bodysuit design donned as a national costume by 2018 Miss Universe Catriona Elisa Magnayon Gray.)

As a diversionary tactic, Magellan ordered two of his men to torch the houses in the nearest settlement they saw called Bulaia. It was effective as other hangaway rushed to their properties. The two Spaniards were caught and killed by the hangaway. The incident enraged our ancestors, causing them to spew countless arrows coming from different directions onto Magellan and his men. Magellan was hit by an arrow on his left leg and a hangaway hurdled a spear on his face, causing his death. It somehow demoralized the Spaniards and with pressures from the attacking hangaway, they retreated to their balanghai.

The battle ensued for an hour, leaving eight Spaniards and four native convert allies from Cebu dead as per Pigafetta. Fifteen in Lapulapu’s force were reported killed because of the crossbow shots. The Spaniards failed to retrieve Magellan’s corpse.

Even Pigafetta himself, who participated in the battle, failed to identify who was Lapulapu among the combatants. Thus, it is uncertain whether Lapulapu was in the battle scene himself. Nevertheless, popular imagery of Lapulapu as a muscular young leader is unhistorical as well.

Deception in Cebu

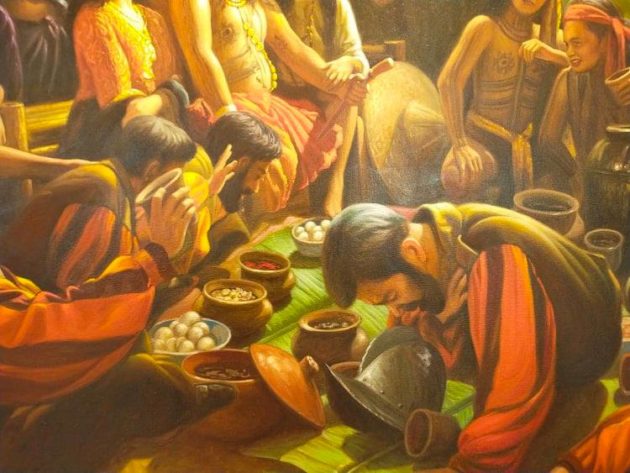

For Enrique de Malacca the death of Magellan meant his liberty. But the remaining officials of the expedition insisted he was still their possession, seeing his invaluableness in communicating with the natives of Southeast Asia. Such was the situation until they reached the Moluccas. Enrique de Malacca then thought of a way to evade the expedition: he plotted with Rajah Humabon to poison the remaining crew of the expedition by inviting them to a feast.

Lapulapu, a Filipino Hero

It is quite unnatural for a country such as the Philippines to commemorate the memory of both Lapulapu and Magellan in 2021. What the Filipino people will commemorate in honor of Magellan is neither his death nor his arrival that marked the Spanish intent to colonize our ancestors, but, rather his perseverance and leadership of an ambitious project that changed world history and the destiny of humanity—the circumnavigation of the world for the first time. On the other hand, Lapulapu was definitely not a Filipino (and would defy to be part of its nascent process in 1565, if he was still alive then); but his descendants redefined the name “Filipino” as a country of over a hundred freedom-loving cultural communities that overthrew the Spanish hegemony and presented themselves as a republic in 1899, defied the U.S. and Japanese imperialism, and became sovereign in 1946. Therefore, Lapulapu and his warriors were heroes of the Filipino nation, the first on the list of our great people.

Bibliography

Escalante, Rene R. National Quincentennial Committee Comprehensive Plan. Manila: National Historical Commission of the Philippines, 2019.

Francisco, Juan R. Indian Influences in the Philippines: With Special Reference to Language and Literature. Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1964.

Gerona, Danilo Madrid. Ferdinand Magellan: The Armada de Maluco and the European discovery of the Philippines. Naga City: Spanish Galleon Publishing, 2016.

Pardo de Tavera, Trinidad H. El Sanscrito en la Lengua Tagalog. Paris: Imprimerie de la Faculte de Medicine, 1887.

Pigafetta, Antonio. Magellan’s Voyage Around the World (3 volumes), James Alexander Robertson, trans. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark, 1906.

Pigafetta, Antonio. Unang Paglalayag Paikot ng Daigdig, Phillip Yerro Kimpo, trans. Manila: Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, 2017.

Scott, William Henry. Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino and Other Essays in Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1992.

_____. Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1984.

About the Authors

MICHAEL CHARLESTON “XIAO” CHUA is a public historian and Assistant Professorial Lecturer of History at the De La Salle University Manila. He is the author of a number of refereed academic journals and a columnist at the Manila Times and Abante. He was the creator of Xiao Time, the history segment of the government television station.

VAN YBIERNAS is an economic and public historian.