Our Ancestors in Bonifacio and the Katipunan

Posted on 11 May 2020

By Ian Christopher Alfonso

One thing we should appreciate about Andres Bonifacio was his consciousness (not only pride) of one’s origin and identity. He, together with the Katipunan, a radical society that projected Philippine independence and self-rule, proudly drawn and stamped on their documents and embroidered on their banners a character from one of the writing systems of our ancestors—baybayin (ancient Tagalog writing system). That character in the Roman alphabet was ‘ka,’ corresponding to the first syllable of the word kalayaan. That word was their equivalent to French liberté, Spanish libertad, and English liberty. The root word is laya, which is present in various Philippine languages referring to either ‘freedom’ and ‘elevation’ (e.g., alaya for mountain among the Kapampangan people [which also means ‘east’]; ilaya for upland or upstream communities among the Tagalogs, which is saraya among the Maguindanaos and daiya to the Ifugaos). From the word, laya comes malaya (‘state of being free’).

Bonifacio himself wanted to be identified as Sinucuan (his Masonic name) and Maypagasa (his Katipunan name). The first one was derived from the mythical lord of Alaya or Mt. Arayat, the princely mountain at the heart of the vast Central Luzon plain. The other name was a conjugation of may pag-asa which means ‘there is hope’ in Tagalog, the language of Manila and its environs; and indeed, their generation was pag-asa (‘hope’).

He also advocated the malay (‘consciousness’) of indigenizing Philippine independence. He wanted each and every Filipino to call one another as kapatid (‘brother or sister’), make damayan (‘mutual or community support,’ similar to our modern-day idea of bayanihan) as a way of life, and begin to acknowledge that they belong to one mother, Inang Bayan (literally ‘motherland’). He instructed his comrades to take good care of one another despite differences in tongue and ethnicity; for he subscribed to the idea that all of us—Sugbuanon (people of sugbu or ‘to walk in the water’), Maranao (‘people of the danao or lake’), Tagalog (‘people of alog or wading into water/people of the ilog or river’), Tausug (‘people of the sug or current’), Subanon (‘people of the suba or river’) or Kapampangan (‘people bordering the pampang or riverbanks’)—descended from our maritime ancestors, thus, we are all water people. That was why he supported the idea of calling the Philippines as Katagalugan (‘land of river or water people’). Even Emilio Aguinaldo, his successor, used Katagalugan and the Philippines interchangeably in various documents.

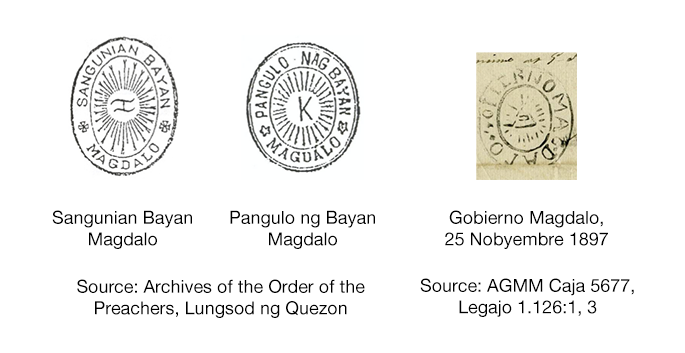

Moreover, he wanted his people and posterity to live under a democracy and a republic. He even used the word Haring Bayan to mean that the bayan (‘people’) are ‘supreme’ (hari). Speaking of hari, Malayan people often associate the word with the sun. And it was not surprising that the Katipunan employed the symbol of the sun, along with baybayin [ka], on its documents, seals, and banners. This Katipunan sun was eventually married to Aguinaldo’s preferred aesthetics: that anthropomorphic sun on the flag and heraldic seals of Argentina. Aguinaldo made it more Filipino (or indigenized) by popularizing a sun rising from behind a mountain range. [Read more about the symbols of the Philippine Revolution here.]

Bonifacio and the Katipunan failed not to repurpose the knowledge about their ancestors. The sacredness of sandugo (‘oneness in blood’) was essential in the ceremonies of the Katipunan. It reckoned the ancient practice among the pre-Hispanic peoples of the country that to forge brotherhood, the two leaders of different communities had to draw blood either from their arms or chest, mixing this in a ceremonial cup with native liquor, and drink afterward. It was called casi-casi among our ancestors in the Visayas and Mindanao, recorded 500 years ago by Antonio Pigafetta, the chronicler of the first circumnavigation of the world. Through this new blood compact among the Filipino people, the Katipunan believed that a new brotherhood had been made among the descendants of Rajah Sikatuna of Bohol and Rajah Soliman of Manila—ancient rulers who entered into a blood compact with the Spaniards in 1565 and 1570, confident that both peoples would acknowledge one another as brethren and equal, which never happened in the next three centuries. Lapulapu and the Victory at Mactan also served as references by the Katipunan to remind their members to not lose hope, for they had a proud history of victory.

It was during Bonifacio’s leadership of the Katipunan that the Philippine Revolution against Spain broke out and proudly showed the world that a new nation was about to rise from the Orient, carrying at their backs not only the dreams of their loved ones but their cultural heritage and history.

Postscript

Our celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Victory at Mactan in 2021 will be more meaningful if we imagine the event being commemorated as among the inspirations that animated the Philippine Revolution of 1896-1899. With that, the Filipino people—the direct inheritors of the memory of Lapulapu and of the Filipino freedom and sovereignty fought in 1896—can celebrate the milestone proudly and with ownership.

Ian Christopher B. Alfonso is a Senior History Researcher of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP). He is a member of the National Quincentennial Committee Secretariat. He is also a Board Member of the Philippine Historical Association and the Secretariat Head of the NHCP Local Historical Committees Network.