Sacrificing a Christmas for the Country

Posted on 24 December 2020

By Ian Christopher B. Alfonso

A lot of us only know Marcelo H. del Pilar since elementary as a hero with an iconic mustache (like Antonio Luna); that he was among the brainchild of the tongue-twisting La Solidaridad; and beyond that, nada. The National Historical Commission of the Philippines pondered this in the animation it produced for the Museo ni Marcelo H. del Pilar in 2016.

Unlike Jose Rizal who wrote volumes of works, del Pilar left the country four, compiled from 1955 to 1970 by the National Library of the Philippines. One of these contains his letter to his wife, Marciana (Tsanay), alone. This volume is a fountain of refreshing facts about the hero: that he was first a husband and a father of two children before he became a great man for his countrymen. In one of the galleries of the Museo ni Marcelo H. del Pilar features parts of del Pilar’s letters to his wife relating how excited he was in experiencing using a public telescope in Paris and saw the outer space; the joy he had upon availing a promo-fare trip (via train) to Paris for the Universal Exposition with his colleagues; the delight of seeing the surroundings of Paris atop the then newly inaugurated Eiffel Tower; and the nostalgia upon tasting sinigang na bangus sa mustasa in Europe prepared by his Bikolano compatriot. It also contains del Pilar’s first Christmas away from home. Dated 24 December 1889, del Pilar wrote his wife from Madrid the following:

Tsanay: a la cinco y media ng hapon dine, ay a las dos na nang gabi rian, nakapag simbang gabi na kayo’t nakapagsalosalo na, kami rine ay uala ng usapan mag hapon kundi ang saya ng pasko rian[;] nakikini-kinita ko si Sofia at si Anita at ang manga bata sa kapitbahay na nasa araw ng kasayahan ngayon. Kun ang loob ko lamang ang masusunod ay magsalosalo na tayo sa paskong darating kung binubuhay.

Translation — Tsanay: It’s 5:30 in the afternoon here, while two in the morning there (in the Philippines); you already have your Christmas eve mass and feast (noche buena). Here, we spent the entire afternoon reminiscing how joyful Christmas Day there. I imagine Sofia and Anita and all the children in our neighborhood are enjoying right now. If only my will be done, I’d like to spend the next Christmas with you.

Del Pilar left the country on 30 October 1888 to escape the wrath of the Spanish friars for organizing a massive rally in Manila requesting the King of Spain to expel the friars from the Philippines. He arrived in Barcelona in January 1889 to help in lobbying in Madrid the reforms needed for the Philippines, especially in the justice system, and in ending the friar supremacy he called frailocracia or soberania monacal. He thought he would finish his campaign in Spain in a year, until he contracted tuberculosis, begging his friends and relatives to lend him money, and worse, picking cigarette butts to ease the cold and hunger. One of the letters from Tsanay contains a one peso coin sent to del Pilar by his youngest daughter Anita just for him to go home. This scene is depicted in a more-than-a-life-size tableau of the father and daughter entitled Bridged by Love by renowned sculptor Willy Layug. It is found in one of the last galleries in the Museo ni Marcelo H. del Pilar.

It is a widely known fact among the historians in Bulacan, that Anita hated her father so much and everything about nationalism. In 1920, the remains of del Pilar was brought back to Manila from Barcelona. While almost everyone was in jubilation, only Anita was unhappy. (Read this beautiful article on Anita.)

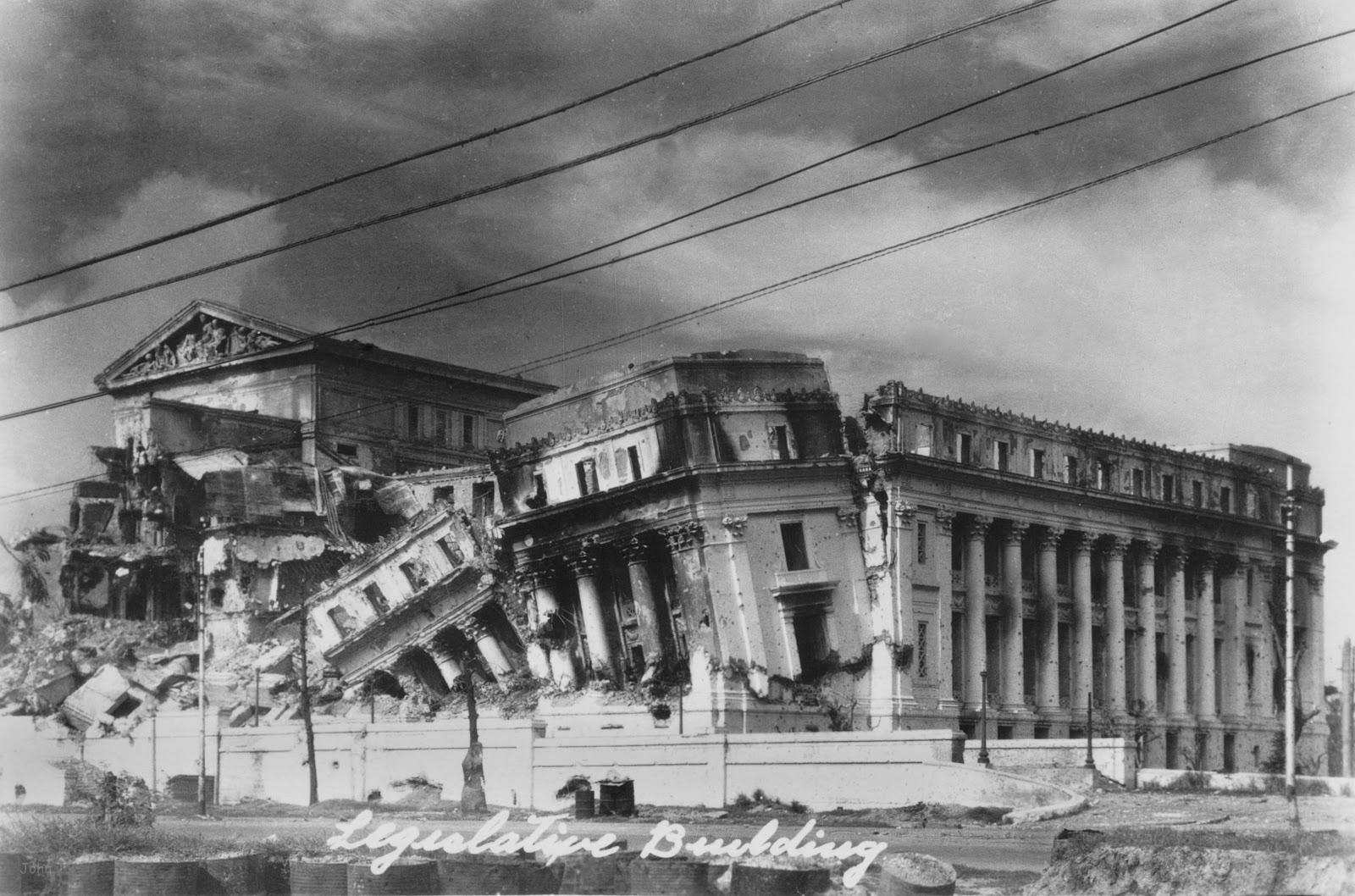

Unfortunately, during the Battle for Manila in 1945, the original letters of del Pilar deposited in the National Museum and Library (at the basement of the Legislative Building) were destroyed, along with other historical and cultural treasures. Until one day, in 1954, educator Dr. Jorge Bocobo surprised the Bureau of Public Libraries (now the National Library of the Philippines) that he had the galley proofs of the two-volume Epistolario de Marcelo H. del Pilar (Letters of Marcelo H. del Pilar) set to be printed if only World War II did not break out in 1941. In 1955, the Bureau published the first volume of the Epistolario featuring the transliteration of del Pilar’s original letters in Spanish and Tagalog to his fellow compatriots in Europe and in the Philippines. Three years later, the second volume was published. The said volume is entirely written in Tagalog and comprises the hero’s personal letters to his wife and to her two daughters. However, only the first volume was reprinted and translated to English in 2004, gaining more public interest in the 21st century. The said edition was published by the National Historical Institute (now the NHCP), the custodian of all the publications of the Bureau of Public Libraries about our heroes since its creation in 1972.

To borrow lines from the late historian Fr. Fidel Villaroel, OP of the University of Santo Tomas Archives about del Pilar’s letters to his family:

Month after month, day after day, for eight endless years (sic, seven years and nine months), the thought of returning to his dear ones was del Pilar’s permanent obsession, dream, hope, and pain. Of all the sufferings he had to go through, this was the only one that made the “warrior” shed tears like a boy, and put his soul in a trance of madness and insanity. His 104 surviving letters to the family attest to this painful situation… (Marcelo H. Del Pilar, His Religious Conversions [Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 1997], 34).

Most probably one has read a number of articles about how Jose Rizal spent his Christmas abroad. But what about the Christmas experience of Rizal’s compatriots in Europe? Does anyone know that del Pilar’s letters to his wife and daughters exist? How about the hero’s first Christmas away from his family because he had to? Presently, we also have millions of del Pilars abroad, far from their loved ones, their home, their country–our overseas Filipino workers (OFWs), also acknowledged by the grateful Filipino people back home as bagong bayani (modern heroes), and the rest of the Filipinos abroad, unable to go home this happiest day in the Philippines. Like del Pilar, et al., they, too, are sacrificing in foreign lands, motivated by their love of family, which is tantamount to the love of country. As Andres Bonifacio said in his Dekalogo ng Katipunan, “Ang kasipagan sa paghahanapbuhay ay siyang tunay na pag-ibig at pagmamahal sa sarili, sa asawa, anak at kapatid o kababayan.”

About the Author

Ian Christopher Alfonso is a Senior History Researcher of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines. He supervises the NHCP Local Historical Committees Network and concurrently the National Quincentennial Committee Secretariat. He is also a Board Member of the Philippine Historical Association.